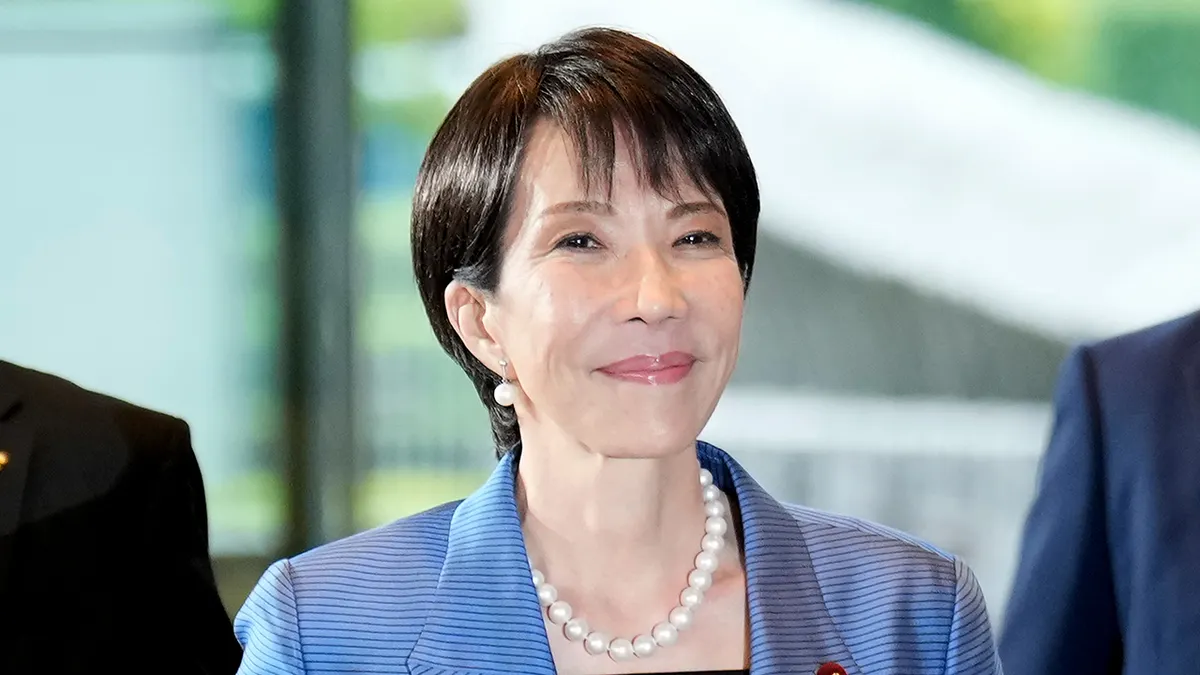

When Japanese voters head to the polls on Feb. 8, they will be voting not only on economic policy, but on the political future of Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, whose personal popularity has come to dominate a closely watched Lower House election.

While bread-and-butter issues such as inflation, stagnant wages and a persistently weak yen remain top of mind for many households, political analysts say the campaign has evolved into an informal referendum on Takaichi herself. Less than a year into office, the fiercely conservative leader has tied her fate directly to the outcome of the vote, betting that her high approval ratings can compensate for the ruling Liberal Democratic Party’s lingering weakness.

“She has made this election about whether voters accept her as prime minister,” said Kazuto Suzuki, director of the Institute of Geoeconomics in Tokyo. “It’s a highly personalized strategy.”

Takaichi has openly acknowledged the stakes. In remarks on Jan. 19, she told supporters she was placing her political future on the line and asked voters to decide whether she should continue to lead the country. The statement was widely seen as an attempt to transform personal support into parliamentary gains for the LDP, whose approval ratings remain far lower than her own.

Polls show backing for the LDP hovering below 30%, even as Takaichi’s personal approval has remained well above that level. That disconnect has shaped the ruling camp’s campaign strategy, with the prime minister emerging as the central figure across party messaging.

“Her calculation is that strong approval and a divided opposition will be enough to deliver a win,” said Mireya Solís, director of the Center for Asia Policy Studies at the Brookings Institution.

The political math, however, has become more complicated. Takaichi now leads an untested coalition with the Japan Innovation Party after the LDP’s 26-year alliance with Komeito collapsed last October. Before parliament was dissolved for the snap election, the coalition controlled only 230 of the Lower House’s 465 seats — a margin so slim it relied on independent lawmakers to function.

The loss of Komeito is particularly significant. For decades, the party played a crucial role in mobilizing voters on behalf of the LDP, and its departure has left the ruling bloc more vulnerable to a coordinated opposition.

Former ally Komeito has since aligned with the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan to form a new centrist force, raising the prospect of tighter opposition cooperation than in previous elections.

Economic anxiety remains a powerful undercurrent. Japan has experienced inflation above the central bank’s target for nearly four years, while real wages have declined annually since 2022. In 2025 alone, real wages fell for 11 straight months, squeezing household budgets already under pressure from higher food and energy prices.

A sharp rise in rice prices last year further dampened public sentiment, and the yen’s renewed slide toward 160 per dollar in early 2026 has intensified concerns about imported inflation. Although exporters have benefited from the weaker currency, many consumers have not.

Still, analysts say frustration over living costs has not translated into widespread anger at Takaichi. Instead, voters appear willing to give her expansionary approach time to work.

“They’re worried about inflation, but they don’t seem to be blaming her directly,” said Ross Schaap, head of research at geopolitical risk firm GeoQuant.

Takaichi has doubled down on fiscal support, unveiling a record ¥115 trillion ($783 billion) budget for the next fiscal year and following through on a large stimulus package aimed at offsetting rising prices.

Supporters argue that her personal story has also broadened her appeal. Financial analyst Jesper Koll of Monex Group has described Takaichi as a rare figure in Japanese politics, particularly among younger voters, citing her rise from a working-class background without traditional political patronage.

Others urge caution in interpreting the vote as a clear endorsement. Kristi Govella, an associate professor at the University of Oxford, said Takaichi’s short time in office makes it difficult to draw sweeping conclusions.

“If the LDP secures a strong majority, it will be because of her popularity alone,” Govella said. “Institutionally and politically, very little has changed since the party’s losses last year.”

Those losses occurred under former Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, whose failed snap election in 2024 cost the LDP its Lower House majority and ultimately his leadership.

With the opposition better organized and the ruling coalition thinner than before, analysts say turnout could prove decisive.

“If turnout is high, it likely benefits Takaichi,” Schaap said. “If it’s low, this becomes a very tight race.”

As election day approaches, Japan’s voters face a choice that extends beyond party labels — one that could determine whether Sanae Takaichi’s personal mandate is strong enough to stabilize her government or whether the country’s political uncertainty deepens once again.